The Bland and the Beautiful: Russia's defeat at Port Arthur in the Anglo-World imagination (1904-5)

- EPOCH

- Jun 1, 2022

- 8 min read

Robert Brown | University of Birmingham

Much like the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war, the Russo-Japanese war (1904-5) saw an overrated Russian military suffer humbling setbacks against an underestimated opponent. Much as with the Russia-Ukraine war, the Russo-Japanese war elicited a flurry of sympathisers, sceptics and charlatans across the Western world and other bystander nations interpreting and tracking the conflict for their own commercial or geopolitical ends. Commercial interests, in particular, drove the Russo-Japanese war to loom large in the Western imagination. Edwardians were raised on a diet of escalating great power rivalry exacerbated by the British Harmsworth newspaper company's campaign to propagate Germanophobia among the British public. Hysterical future war fiction such as William Le Queux's million-copy selling The Invasion of 1910 (1906) imagined a German attack on London, and H.G Wells' The War in the Air (1908) explored frightening new weapons technologies. In this cultural atmosphere, the spectacle of all-out mechanised war in Manchuria shifted tickets and memorabilia like nothing except the major cricket or football fixtures.

The article focuses on some of the more unusual ways the war was narrated and even objectified by creative and savvy entrepreneurs throughout the English-speaking world. From Bland Holt's melodramatic romance at Port Arthur to the Pain family's bombastic firework re-enactments of the siege of the city, the article explores a snapshot of pre-cinema culture in which a bizarre melange of styles and stereotypes competed to provide audiences with a war experience that was anything but bland.

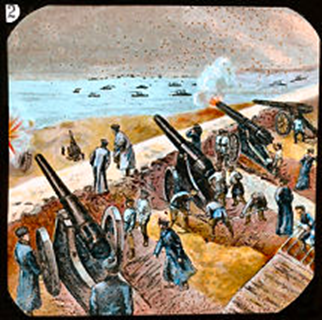

After years of bitter contention between the Empires of Russia and Japan over control of the Liaodong Peninsula, Manchuria, Russia occupied the Peninsula and constructed Port Arthur naval base in 1897. This proved intolerable for Japan, and on 8-9 February 1904, they finally struck, as Admiral Togo launched a surprise attack on the Russian fleet anchored there. The engagement and ensuing siege quickly gained international status as a gruelling cauldron of modern battle. The spectacle of large naval battles and massive artillery duels became a focal point for media attention, commemoration, and later theatrical re-enactment.

Japanese victory in the Battle of 203 Metre Hill, overlooking the city harbour, proved a turning point. From here, artillery spotters directed a devastatingly accurate bombardment of the bottled-up Russian fleet. Russia's Pacific fleet was destroyed or interned, while the Japanese Army systematically mined and captured key Russian forts. The situation hopeless, Port Arthur finally surrendered.

John Dower, in War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (1986) has described the Russo-Japanese conflict as the 'well-watched war'. Military observers from Britain, Germany and all major powers flocked to view and write about the battlefields of Manchuria. The Great Powers all weighed up the impact of a Japanese victory on their geopolitical interests. The siege of Port Arthur particularly gripped the Western and English-speaking press, with up-to-the-week reports of battles, troop dispositions and comparisons of armaments and technologies. Existing cultural stereotypes of Russia and Japan became lenses through which much of the geopolitical coverage and theatrical reproduction of the siege was refracted. Tropes of Russophobia, Japonisme and the 'yellow peril' collided with mass-market entertainment to produce some often bizarre and eclectic results.

Coinciding with a 'picture postcard boom', the artists and distributors of mass-circulation illustrations and photographs cleverly calibrated their output to appeal to the geopolitical tastes and cultural mores of their respective national markets. For France, who helped finance the Russian war effort, or Germany, whose Kaiser Wilhelm II felt Emperor Meiji's growing empire represented an evil 'yellow peril', expanding Japan represented a nightmarish subversion of a Eurocentric racial and geopolitical status quo. Reflected in vividly illustrated postcards, this revulsion is vividly documented in the MIT visualising cultures project.

Lanterns slides encompassed a broad umbrella of painted, printed, or photographed images on glass viewed by projection. Philadelphia daguerreotypists William and Frederick Langenheim patented thy Hyalotype (hyalo meaning the Greek word for glass) in 1850. These were the one form of visual media in 1904-6 that really crossed the entrenched cultural boundaries between Western and non-Western societies. Between the Sino-Japanese (1894-95) and Russo-Japanese war saw the height of their popularity as news and entertainment media. The Junior Lecturers Slide Series produced by W. Butcher & Sons of London projected Manchurian battle scenes to a mass audience. In Japan, the lantern slide show was also utilised to promote 'wartime mobilisation campaigns'.

One such lantern slide, according to Winnie Won Yin Wong marked a turning point in the life of Lu Xun, a Chinese medical student at Sendai Medical Academy in 1906. Microbiology lectures were delivered using lantern slides, and after classes they were used to show eager Japanese students the progress of the war. As the only Chinese student, Lu Xun had to watch his classmates applaud an image of a bound Chinese man about to be executed by the Japanese for being a Russian spy. Deriding the docility of the Chinese onlookers in the picture, the spectacle of barbarity drove Lu Xun to reject Western medicine, becoming one of China's most foremost revolutionary writers. In a modern parallel, 2006 saw a protest from overseas Chinese students against the MIT Visualizing Cultures project. Again in a pedagogical setting, digital images and descriptions of a woodblock triptych depicting Japanese beheadings of Chinese soldiers in the first Sino-Japanese war (1894-5) were perceived by the students to carry a problematic ideological agenda.

Particularly in Britain, Russophobia had a well-worn tradition through the Great Game antagonisms over imperial influence in Central Asia, and the titanic battles of the Crimean war that thwarted Russian expansionism. However, Japonisme and the 'yellow peril' were newer developments in the Anglo-World lexicon. Japonisme is a term that reflects the explosive popularity of Japanese art, design, and aesthetics in the West after the opening up of Japan in the 1860s and 1870s. From 1902 Britain and Japan were allies, and these tropes coalesced to form an aura of fascination and a culture of respect surrounding Japanese martial prowess and cultural sophistication. The 'yellow peril' was a far more sinister vision of Japan and East Asian peoples. Numerous newspaper articles and dime science fiction novels extrapolated nightmare narratives of European Imperialism upended and replaced with Japanese hegemony over the pacific.

At London's Covent Garden on 18 February 1904, however, Russophobia and Japanophilia were the clear emotions on display. Less than two weeks after the Japanese attack on Port Arthur, the Daily Illustrated Mirror reported on18 February 1904 a fancy-dress variety ball. The costume dress code was designed to represent various ideas in connection with the war. However, 'unluckily for some of the wearers,' it was noticed that hints of 'Russian dress, or any suggestion of the Russian Bear, called...forth groans and hisses,' from guests and onlookers. On the other hand, those who 'affected anything pertaining to Japan were 'literally hugged by the delighted onlookers, and received an ovation, wherever they went.' The paper expressed great surprise that 'these heroes of the night had to bear the brunt of the storm of popular approval before they could make good their escape'. This spontaneous display at Covent Garden suggests that London high society, at the very least, was taking a partisan if passing pro-Japanese interest in early events.

One place where directors, producers and impresarios are a little more reluctant to go in representing modern war, barring exceptions such as the charming Their Finest (2017), is comedy-romance. In the pre-cinema era, however, melodramas and comedies were common, and these productions often cannibalised and spliced together tropes to produce fanciful narratives. One such example was the melodrama, Besieged at Port Arthur. Produced by Arthur Shirley and Sutton Vane, and written by Bland Holt, it was performed at Theatre Royal in Sydney throughout 1906.

Joseph Thomas 'Bland' Holt was an Anglo-Australian impresario, entrepreneur and actor steeped in Australian theatrical tradition. Born in England in 1851, his father was an actor-manager who took the family to work in Melbourne in 1854. By age fourteen, Bland was a professional actor. By 1876 he was settled in Australia, winning fame as the 'Monarch of Melodrama' who both acted as a comedian in his own plays alongside his second wife Florence Anderson, and employed an eclectic array of special effects such as a balloon ascents. His success lay in adapting plays that had succeeded in London and the United States for an Australian audience, such as For England in 1896, based around British campaigns against the Boers in the First South African war, and including several sporting as well as military scenes.

Opening at the Sydney Theatre Royal on 14 April 1906, according to Margaret Williams in Australia on the Popular Stage, Holt used projected documentary film footage of the Russo-Japanese war in some scenes instead of a back-cloth. The curtain was raised for the first act in the chief ballroom at Port Arthur. This was an international affair, as Russian chief of Imperial spies Ivan Marski, played by actor Frank Norman, vowed to win the love of Japanese lady Saydee Orama (Frances Ross) by destroying her lover, the hard gambling British army surgeon Frank Forrester, played by Walter Baker. Bland Holt and Florence Anderson also appeared in the action as comedic journalists Lal Ray and April Showers.

As the ball was in full swing, the Japanese fired the first shell of the siege in a cinematic scene, terrifying the unprepared revellers. As Marski's machinations to win Saydee and her rich father's money played out, in scene three the melodrama rapidly moved from a well-laid romantic plot to bombastic military sensationalism. In a feat of dramaturgy, the stage was opened up and flooded for mock naval battles between the fleets. A mechanical Japanese submarine worked its way into view and dramatically sank the Russian flagship, Petropavlovsk, loosely following historical events. Much like the sinking of Russia's flagship Moskva in 2022, this was one of the highlights of both the show and the conflict. With Holt's comedy element, although it may seem in poor taste by later standards, his melodrama successfully meshed superficial Japonisme with romance and mock warfare while sidestepping complex geopolitics.

One night in September 1905, a plucky local reporter for the Minneapolis Journal had taken on the role of civilian war correspondent. Furnished with a long army overcoat and cap, he was instructed to make his way up the Port Arthur battlefront. Such was the hellish ferocity of the bombardment he witnessed that even after escaping unscathed, the reporter 'dreamed all night of crashing shot and bursting shell, of sinking warships and whole cities in flames.' The horror of such a spectacle stayed with him, and even a 'pencil falling on the floor…and the slamming of a door' would send him into a post-traumatic 'hysteria' of palpitations.

However, something was wrong. The buildings and warships were somehow made of canvas and wood rather than steel and stone, and the heavy ordnance, was a mixture of dynamite and nitro-glycerine. Those discharging explosives were not Russo-Japanese artillerymen and naval gunners, but some thirty pyrotechnists co-ordinated by director Emil Capretz. Finally, this was not at Dalian, but located deep in the heart of the American Mid-West at the Minneapolis State Fair. In fact, this was 'Pain's Port Arthur', a centrepiece production of James Pain junior and his son Henry J. Pain. The Pain's Port Arthur spectacles were specifically 'modelled' or 'al fresco' painted canvas panoramas simulating the Manchurian battle zone, set up outdoors in large pleasure gardens, sports fields or exhibition grounds. These outdoor panoramas were modelled much like a movie set with large props of wood and plaster and offered the historical-narrative backdrop against which the massive fireworks displays took place for a viewing public.

They oversaw a continent-spanning fireworks empire, the Royal Alexandra Palace Fireworks Company (shortened to Alexandra Palace Fireworks Company in the United States). Their American base of production was at the Greenfield, L. I. fireworks factory, New York. In addition to using their own 10,000 seat purpose-built arena at Manhattan Beach, from 1904-6 the show visited Nashville, Chattanooga, St. Louis, Detroit, and Buffalo (New York). On top of this, in addition to re-enactments in London and Manchester, James Pain Junior presided over an ambitious tour of the 'Port Arthur' spectacle throughout Australia and New Zealand, stopping off at all the state capitals of Australia in addition to smaller venues.

The article explored a snapshot of pre-cinema culture, which sought to provide audiences with unsubtle yet fascinating simulacra of conflict and mock warfare. Such a plethora of different imaginings, from postcards to pyrotechnics, did not necessarily form a coherent, stable genre in the way they historicised the Russo-Japanese war. The ephemerality of some of these spectacles, the destructible panoramas, the poorly curated or discarded props and theatrical playbills, have made the incorporation of military spectacles into wider histories of conflict problematic. However, they represent a fascinating window into the raucous tastes of Edwardian publics.

Dr. Robert Brown is a Teacher of History at Harrow International School, Beijing. His PhD from the University of Birmingham focused on the intersection between racial science, immigration restriction and the ‘yellow peril’ within the British Empire. He continues to write and publish in journals and magazines.