Playbills: the 'Faded Love-Letter' to Early Modern Theatre

- EPOCH

- Dec 2, 2020

- 6 min read

Updated: May 27, 2022

Abigail Robinson | University of York

'The casual sight of an old playbill, which I picked up the other day – I know not by what chance it was preserved so long. It presents the cast of parts in the Twelfth Night, at the old Drury Lane Theatre, two-and-thirty years ago. There is something very touching in these old remembrances. They make us think how we once used to read a playbill… spelling out every name, down to the very mutes and servants of the scene. “Orsino, by Mr. Barrymore.” What a full Shakesperian [sic] sound it carries! How fresh to memory arise the image, and the manner of the gentle actor!’

–Essays of Elia, 1823

Despite the two hundred years which have elapsed since these words were first penned by Charles Lamb, time has done little to blemish their poignant evocation. He offers a very authentic and effective description of an early modern British playbill. Present-day definitions identify them more pragmatically as a poster, piece of paper, program, announcement, or advertisement of theatrical performance. Although their origin is unclear, it is likely that production began in the late sixteenth century. In an effort to fully leverage their potential, theatre managers ensured that playbills were a significant feature of everyday life during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. They were posted on the walls and doors of English cities, handed out in the streets, printed in newspapers and, in some areas, delivered by hand to homes and businesses. By 1800, individuals known as bill-stickers were employed specifically for the purpose of distribution. Prior to this, it was the cast who would circulate playbills around the town. In his memoirs, renowned actor and Yorkshire theatre manager, Tate Wilkinson, recalled witnessing this ‘horrid custom’ around York and Hull, where performers would ‘knock humbly at every door… and obediently stop at every shop and stall to leave a playbill’.

Despite the large, and therefore cost-effective, batches favoured by the printing houses, very few playbills survive from this early period due to their vulnerability. They were printed on flimsy paper (known as ‘silver paper’) and largely affixed outdoors to endure the English elements. Once a performance ended, the corresponding playbill often followed – lost, destroyed or, in some cases, adapted to serve household endeavours. For example, during a period when it was fashionable for women to wear their hair in ringlets, playbills proved very successful as ‘curl-papers’. There are several references to the use of curl-papers in Oliver Twist but, in Nicholas Nickleby, Charles Dickens specifically illustrates this resourcefulness, describing a ‘scattered litter of curl-papers… together with a confused heap of playbills.’ Another application where playbills excelled was as a ‘spill’ which, unfortunately, described their use as a firelighter.

Thankfully, by 1750, playbills were widely considered to be a fashionable collectable outside of the professional theatrical community. This continued into the nineteenth century and, by 1888, a single bill associated with David Garrick, one of the most influential figures in theatrical practice of the time, could be sold for ‘one or two guineas’. A series of chronologically consecutive bills from a well-known playhouse, such as Drury Lane, could fetch a great deal more. Although, it would have been very difficult to procure a full series on account of their brief life cycle and, in a city with many theatres (such as London), the sheer amount on display at any one time. During a single working day, bill-stickers were expected to display playbills in up to two hundred areas of the city! Unfortunately, towards the end of the nineteenth century, playbills vanished and were replaced by the more familiar and recognisable theatre programmes and posters which accompany English performances today. However, for those interested in expanding their knowledge of British culture, either for leisure or research, these fascinating single sheets present a superb opportunity. Sadly, playbills have faced historical neglect when compared with other forms of ephemera (such as ballads), and the scholarly work which does exist is overwhelmingly London-centric despite the survival of many provincial playbills. The theatre was a pervasive part of early modern British life and the Yorkshire circuit, for example, was one of the most important in the country.

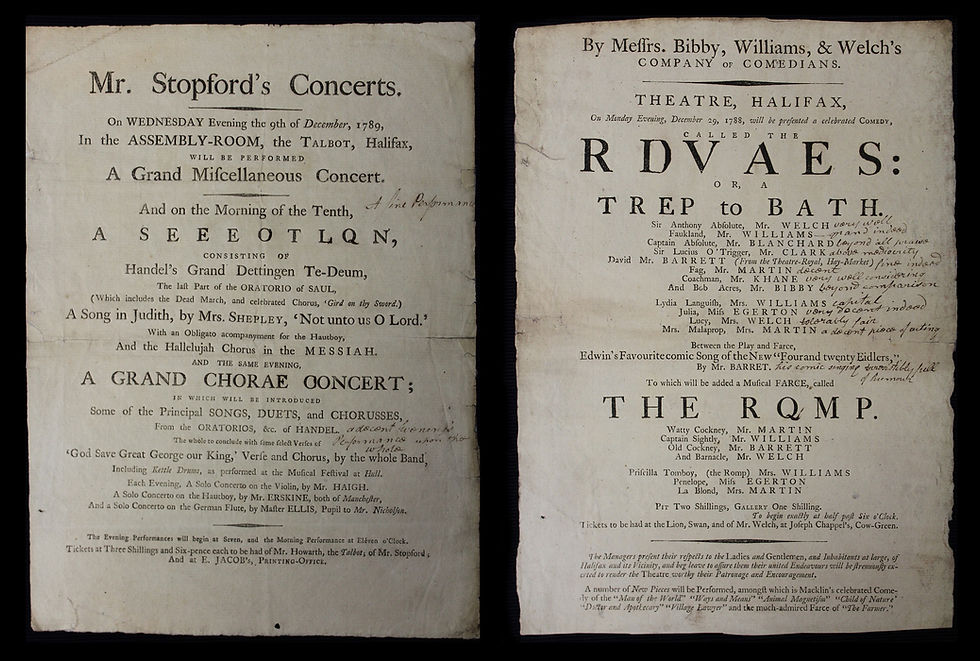

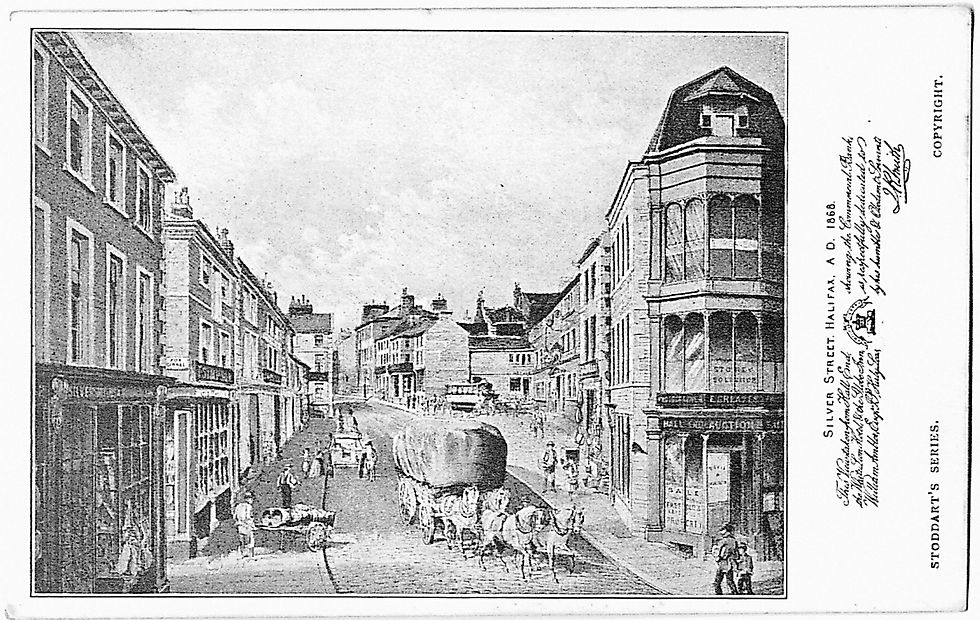

The playbill selected for this article, dated Monday 29th December 1788, advertises a performance of ‘The Rivals’ in Halifax, West Yorkshire. This comedy of manners was hastily written in late 1774 by the 23-year-old Richard Brinsley Sheridan and first performed in Covent Garden, London, in 1775. Unfortunately, many were disparaging of its opening night, unhappy with the quality of the acting and excessive length of the play. It ran one hour over schedule, some of the cast forgot their lines and the actor playing Sir Lucius O’Trigger offered such a poor and offensive performance that a member of the audience threw a piece of fruit at him. However, Sheridan addressed the criticism and, eleven days later, a revised second performance was met with praise. In Halifax, three years on, the playbill describes the show as a ‘celebrated comedy’. One of the main industrial and commercial areas in West Yorkshire, Halifax’s township had a population of around 7000-8000 and an emerging middle class by the end of the eighteenth century. As early as 1759, there are references and reviews in local newspapers, such as the short-lived Halifax Union Journal (1759-1760), about theatrical performances. However, it is playbills that offer the most thorough and consistent timeline of the Halifax theatre scene. Although daily local newspapers would publish the details of that evening’s intended performances, it was not uncommon for last-minute changes to be made to the location, start time, cast or play itself. As playbills were printed later in the day to allow for possible amendments by the theatre managers, they provide a much more accurate record of which performances were performed when. By 1790, when the first purpose-built theatre was erected, the town had developed something of a tradition of theatregoing, receiving annual visits from travelling companies, strolling players and ‘barn-stormers’, since at least the 1750s, who performed their shows in various local settings. This is evidenced by surviving playbills from Halifax which can be traced back to 1758, announcing performances at ‘The New Theatre at the Talbot’ and the ‘Theatre in the Old Cock Yard’. Inns and assembly rooms such as these were frequently used, and barns were also considered ideal due to their large open yards or other enclosed spaces acting as a ready-made auditorium. It is possible that the ‘theatre’ referred to in this playbill was the White Lion, 7 Silver Street, as it was a regular venue for dramatic performances and referenced in different playbills during 1762. Although, in many respects, this playbill represents a quintessential eighteenth-century offering, it is rare to find handwritten annotations and amendments this extensive. However, there is one other example in York Minster Library of a kindred Halifax playbill featuring comments in the same handwriting. Although the author is currently unknown, the language used indicates an educated, learned individual who may have been a critic or talent scout with an interest in Halifax dramatics. It is interesting to wonder why the letter amendments (‘RDVAES’ instead of ‘RIVALS’, ‘Trep’ instead of ‘Trip’, ‘RQMP’ instead of ‘ROMP’, ‘Eidlers’ instead of ‘Fidlers’) have been made. An exploration of newspapers in the region, such as The Leeds Intelligencer or Yorkshire Freeholder, may reveal an entry (such as a review) which relates to this particular playbill and sheds light on the author or their intentions. In 1913, British historian William Lawrence spoke of the power of playbills, stating that ‘the play was no longer the thing’. They are exceptionally varied in form and content and have the ability to offer huge insight into how theatre affected, and was affected by, our social and cultural preferences. Far removed from the once-held belief that a playbill lost all value once its corresponding play was over, it has been suggested that no other source offers more information about early modern theatre. ---------------------- Further reading

Gowen, David, 'Studies in the History and Function of the British Theatre Playbill and Programme 1516-1914' (PhD diss., University of Oxford, 1998).

Fitzgerald, Percy, 'The Play-Bill: Its Origin and Development', Gentleman’s Magazine, 264 (1888).

Lawrence, W., 'Old Playbill', The Connoisseur, 18 (1907).

Stern, Tiffany, ''On each Wall and Corner Poast': Playbills, Title-pages and Advertising in Early Modern London', English Literary Renaissance, 36, no. 1 (2006).

Russell, Gillian, ''Announcing each day the performances': Playbills, Ephemerality, and Romantic Period Media/Theatre History', Studies in Romanticism, 54, no. 2 (2015).

The British Library are currently running their ‘In the Spotlight’ project, aiming to make playbills from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries digitally accessible and more findable online for those interested in these fascinating documents. Their crowdsourcing project is still open, allowing members of the public to be involved in transcribing titles, names and locations to make sourcing playbills easier for everyone. Potential contributors can find out more here: https://www.libcrowds.com/collection/playbills. Those interested in the 1788 Halifax playbill can make an appointment to view it through the Special Collections & Archives facility at York Minster Library. Abi Robinson is a current MA Early Modern History student at the University of York. Robinson’s research interests lie broadly in early modern British history and this article is based around preliminary research for her dissertation, entitled ‘"The play was no longer the thing": a study of early modern Yorkshire playbills’. Twitter: @abimrob