James Peate | University of Bristol

The 1753-1754 case of Mary Squires, a Romani woman convicted and later acquitted of kidnapping maidservant Elizabeth Canning, was one of the most famous English criminal cases of the eighteenth century. The case centred on eighteen-year-old Canning, who disappeared for twenty-eight days in January 1753. On her return, Canning, covered in dirt and bandaged with a rag from a wounded ear, explained her plight, leading to the arrest of Mary Squires and Susanna Wells.

In her testimony in the trial of Wells and Squires, Canning claimed to have been robbed, bound, and assaulted with a blow to the temple by two men in greatcoats. The men dragged Canning to the house of Susanna Wells (who was not present during Canning’s alleged confinement) where she was confronted by Mary Squires. According to Canning, Squires ‘took her by the hand, and asked me if I chose to go their way’, an insinuation that she become a prostitute, offering her fine clothes if she agreed. Unhappy with her answer, Squires slashed Canning’s petticoats and confined her in a loft with only a quarter loaf of bread, until twenty-seven days later when she was able to jump from an upstairs window and escape.

Figure 1: Etching of Mary Squires from 1753 or 1754 by Thomas Worlidge (National Portrait Gallery)

Because assault was a civil matter, the case was instead pursued as one of theft of the petticoats Squires had slashed, which being the value of ten shillings meant that if found guilty Squires would face execution. Despite bringing forth a witness who testified to Mary being elsewhere during the alleged kidnapping, she was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging.

In the aftermath of her trial, reports suggested that Squires was ‘dangerously ill’ with goal fever (now known as typus) caught during her stay in prison, however, she would not be executed. The trial’s judge, Lord Mayor of London Sir Crisp Gascoyne, had been unhappy with how the trial had proceeded. He was upset that Canning’s supporters had prevented witnesses for the defence from appearing and he was unconvinced by Canning’s testimony. His investigation found that the primary witness for the prosecution, Virtue Hall, had only agreed to testify under the threat of arrest from Henry Fielding – writer of Tom Jones and by 1753 a magistrate. This revelation aided Gascoyne’s investigation in obtaining a pardon for Squires and resulted in Canning being tried and found guilty of perjury. She was transported to America, where she died in 1773.

By the early 1750s, racist attitudes towards Romanies had thawed from points of significant tension in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when vagrancy laws had been introduced that made being Romani punishable by death. Prior to the Squires case, these racist attitudes were mostly forgotten, and many of the offensive tropes and stereotypes appeared less prevalently in print.

Yet despite Squires’ acquittal, the case brought forth a wave of antiziganism in a media storm of newspaper stories, satirical prints, and pamphlets that were printed on the case. Although Squires had her defenders, (the London Daily Advertiser, for example, printed letters questioning the case and supporting Gascoyne’s investigation), there was greater support in print for Canning. Much of this support focused on tropes based on Squires’ Romani ethnicity and lifestyle. There are numerous published accounts in which Squires is referred to more often as ‘the Gypsy’ than by her own name, defining her solely by her ethnicity. For example, a letter printed in the Gazetteer newspaper named Canning and Wells throughout, while referring to Squires only as ‘the Gypsy.’ Newspaper reporting of her trial also ensured that Squires’ ethnicity was always mentioned, referring to her as ‘Mary Squires, the gypsy.’

Some of the more egregious material was printed by supporters of Canning, who dubbed themselves ‘Canningites.’ These supporters made allegations that Squires had kidnapped Canning either to make her a prostitute or a gypsy, because of their ‘desire of encreasing the Train of Gypsies.’ But the Canningites were not content with tropes of child stealing and forced assimilation, they also called for enforcement of the earlier vagrancy laws that criminalised gypsies and carried the punishment of death. One Canningite pamphlet, while calling for the enforcement of these laws, declared that ‘Had the gypsey happened to have been hanged the Consequence would have been, that there had been in the Nation one Vagabond less.’

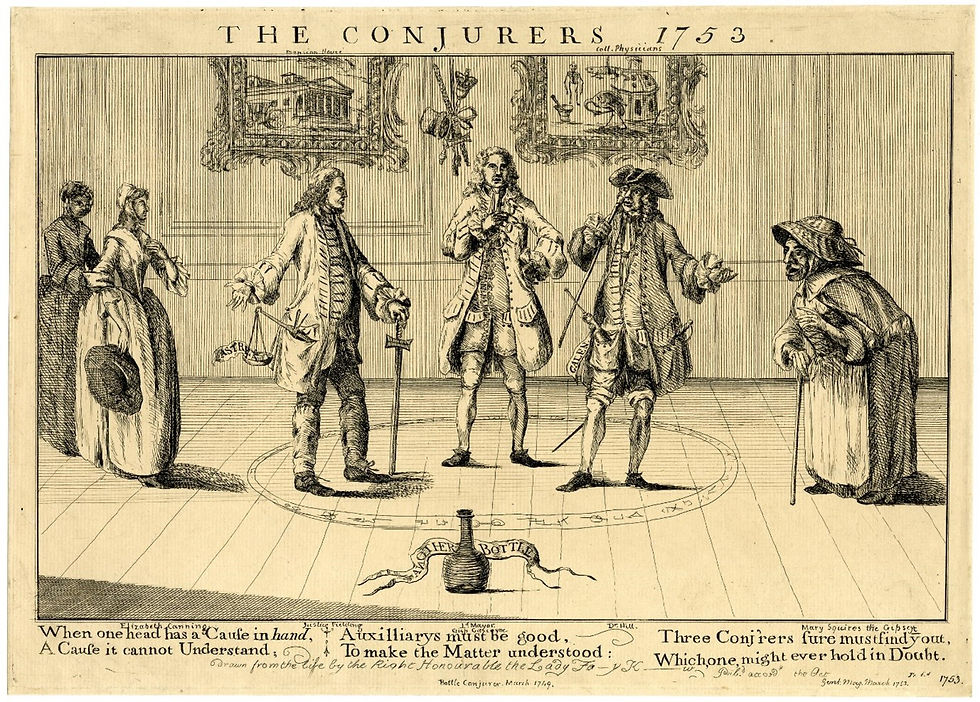

Figure 2: Satirical Print The Conjurers, from 1753, is an example of how Squires (far right) was portrayed as a witch and a magic user (British Museum)

In graphic print, Squires is portrayed as dark-skinned and broad-featured, compared to the pale and more slender Canning. But more than looking to emphasise the aesthetic differences between Squires and Canning, prints looked to stereotype Squires as a witch. In other material, she is shown flying on a broomstick and conducting magic within ritual circles to obtain her innocence.

These tropes were not applied to Squires alone but to Romanies more generally and lasted beyond the immediate aftermath of the case. A print from later in the century, The Wife's Fortune Told, depicts a Romani woman almost identical to Squires with her distinct hat rather than more stereotypical headscarf, and a baby strapped to her back, about to begin telling a fortune. The use of this image demonstrates a merging of existing stereotypes of Romani as fortune tellers and child kidnappers, while showing Squires’ influence on the persistent image of a stereotypical Romani.

Figure 3: The Wife's Fortune Told shows a Gypsy woman almost certainly based on Squires

The tropes and themes stoked up by the Squires case reignited previous stereotypes of Romani people bringing them once more to the forefront of public consciousness. This can be seen even as far as Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language, 1755: the definition for ‘Fo’rtunetell’ included a quote from Walton’s Angler which stated, ‘The gypsies were to divide the money got by stealing linen, or by fortunetelling.’ Whilst we cannot be certain this was directly influenced by the Squires case, there does appear to be an increase in Romani stereotypes within printed material in the years after 1753, which was likely influenced by the publicity the case received.

Offensive stereotypes and tropes of the past can often seem ridiculous to more modern sensibilities. but the resurgence of Romani tropes and themes used to attack Mary Squires in 1753 are prescient given their endurance. The importance of the resurgence of antizigansim during the Squires case is significant to note, even in a context of improving sensibilities through the rest of the eighteenth century. Despite the generally improved attitudes towards Gypsies, which helped lead to the repeal of the vagrancy laws that persecuted Romanies in 1783, the tropes and stereotypes highlighted by the Squires case became reintegrated into anglophone society.

The twentieth century showed how harmful acceptable tropes and stereotypes can be when incited into populist racism. Roma and Sinti peoples were killed in their hundreds of thousands by the Nazis in the 1940s. Even in twentieth-century children’s media, the same harmful tropes and stereotypes that were levelled at Mary Squires in the 1750s are still present. Disney has often leant on many of the tropes and stereotypes across different media. In Robin Hood (1973), Robin and Little John dress up as the stereotype of Romani fortunetellers while stealing money from Prince John. Despite abandoning Hugo’s tropes from the book of Romanies as child kidnappers, assimilating the kidnapped, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996) still shows Romanies as fortune tellers and magic users throughout. Whereas other racially offensive works such as Dumbo and Aladdin feature content warnings on Disney’s online platform, Disney+, those with offensive Romani tropes contain none. More overt antiziganism is equally seen as acceptable within the media. In 2022, comedian Jimmy Carr joked that Roma and Siniti deaths in the Holocaust were ‘positives’ on a Netflix special. Although receiving some condemnation on social media, this did not arise until two months after its release and Carr was defended strongly by fellow comedians and his special remains on Netflix.

The resurgence of antiziganism stoked by the case of Mary Squires is pertinent even today. Although overt antiziganism appears mostly dormant in the early eighteenth century, the ready acceptability of the tropes, stereotypes, and themes applied to Romani people made the wave of antiziganism aimed at Squires and Romanies of the 1750s easy to provoke. These tropes and stereotypes remain acceptable in the media today and are arguably more prevalent than they were in the 1750s. Because of this, the case of Mary Squires retains its relevance two hundred and seventy years after she was tried.

Further Reading:

Cressy, David, Gypsies: An English History, (Oxford University Press, 2018)

Houghton-Walker, Sarah, Representations of the gypsy in the Romantic period (Oxford University Press, 2014)

Le Bas, Damian, The stopping places: a journey through Gypsy Britain (Chatto & Windus, 2018)

Okley, Judith, The Traveller-Gypsies (Cambridge University Press, 2009)

James Peate is an Early Career Researcher in social and cultural history, with a focus on the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. His research interests include the development of the eighteenth-century mediascape and the role of populism in early movements for parliamentary reform. He currently researching representations of Romanies in eighteenth and nineteenth-century culture.

Twitter: @JamesEPeate