Isobel Bloom | University of Wisconsin-Madison

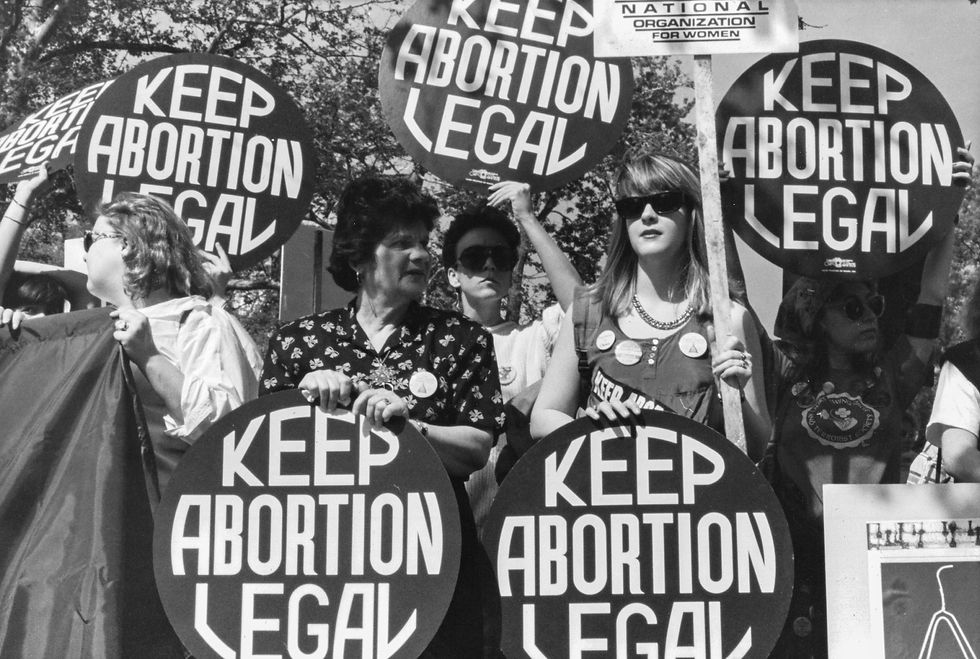

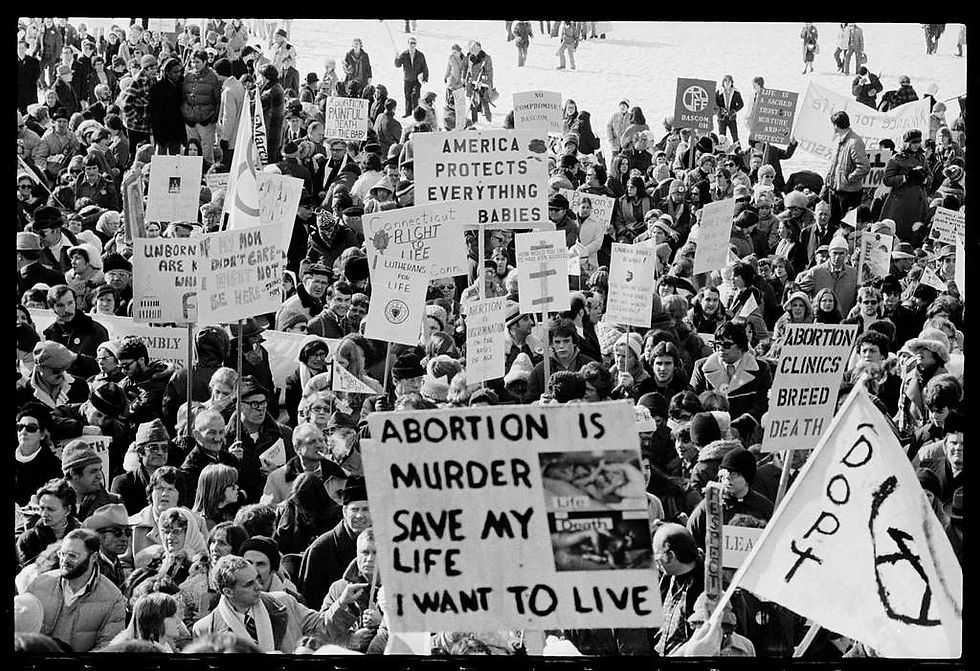

In January 1979, Eleanor Smeal, president of the National Organization for Women (NOW), a grassroots feminist group active in the United States, proposed a meeting of abortion rights supporters and detractors. Fearful of the consequences of growing animosity on either side of the abortion debate, she insisted that opposition leaders ‘had a responsibility to meet and begin a dialogue’. Smeal’s suggestion that abortion activists could engage in civil discussion was exceptional in a climate characterised by increasing entrenchment on the topic. Though it was not until 1980 that the Democratic Party endorsed Roe v. Wade (1973), the former US Supreme Court decision that legalised abortion, a partisan culture surrounding abortion had swelled since the early 1970s. Alongside this political shift, hostilities between pro-choice and anti-abortion activists had intensified, often resulting in violent clashes. Given this context, as well as the profound moral and ethical conundrums at the heart of the abortion debate, how can we make sense of Smeal’s coalition building attempts? And how might a focus on these efforts shift our understanding of the US abortion wars?

Smeal’s gathering of anti-abortion and pro-choice leaders was no small feat given the reticence of many activists to concede any moral or political ground to their adversaries. But Smeal did not anticipate that attendees would abandon their convictions. Instead, she believed that, by finding consensus on issues other than the absolute question of abortion legality, pro-choice and anti-abortion leaders could reduce cross-conflict tensions. She envisioned them coming together ‘to seek ways to lessen the need for abortion, to reduce the incidence of unwanted and troubled pregnancies, and to end the increasing polarization and violence that surrounds this issue’.

Although the 1979 NOW meeting ended in disharmony, Smeal was not alone in the quest to engage her adversaries in civil dialogue. Recognising that extremism – in both rhetoric and action – interfered with reproductive decision making, others too sought ‘common ground’ on abortion and related issues in the years to come. The endurance of these collaborative efforts suggests that the absolutisms propagated by the abortion wars provides an inadequate framework for understanding reproductive activism in the US. This is because some activists, understanding the limited utility of continually clashing with their opponents, willingly put their abortion politics aside to improve other areas of reproductive healthcare.

On February 15, 1979, just three weeks after Eleanor Smeal’s initial invitation, NOW held a meeting for pro-choice and anti-abortion leaders at a hotel in Washington DC. Attendees included representatives from the National Abortion Rights Action League, Planned Parenthood, the Right to Life Crusade, and the National Right to Life Committee, as well as smaller pro-choice and anti-abortion groups. Though NOW’s facilitation of a forum for abortion opponents and supporters was initially applauded by some observers, their decision to refer to those opposed to abortion as ‘anti-choicers’ irked their political adversaries before the event had even begun. As right-to-lifer Juli Loesch Wiley put it, ‘the term “anti-choice” in the NOW invitation… was unfortunate… You would not like to be called “anti-life”’. Loesch Wiley also complained of unbalanced representation, lamenting that because the anti-abortion ‘side’ was precluded from NOW’s agenda-setting, the pro-choice ‘side’ was given ‘the advantage of defining the meeting itself, defining the participating groups… and seemingly defining the priorities and perceptions of the group’.

Clashes at the 1979 NOW meeting extended far beyond semantics and unequal opportunities for organising. A protest by three women members of the Cleveland, Ohio chapter of People Expressing Active Concern for Everyone (PEACE) – Mary O’Malley, Nancy Hackle, and Jean Matava – cast into serious doubt the possibility of fostering any meaningful collaboration. These anti-abortion activists felt that, by announcing their plans for a meeting on the day of the March for Life, the largest annual gathering of right-to-lifers in the US, NOW revealed their intent to ‘examine and evaluate’ the anti-abortion movement. Operating under this assumption, as well as the belief that there could be ‘no possible motive for any pro-life person to sit down and negotiate with people who had been instrumental in the initial legislation and routine taking of human life’, the PEACE-Cleveland members decided to sabotage the meeting. Reflecting their understanding of the power of anti-abortion visual imagery to shock and disturb, they acquired the remains of two Black female fetuses, both of whom were allegedly aborted, before travelling to DC. The women activists then waited until the end of the NOW meeting before displaying the fetal remains to attendees. ‘In Eleanor Smeal’s press release, she mentioned that the true victims of the violence of abortion are females, especially the young and the poor’, Hackle told the press while Matava uncovered the bodies. ‘We have brought with us two young, very young females who are the true victims of the violence of abortion’.

Some anti-abortion activists were supportive of the protest by PEACE-Cleveland, including those who accused NOW’s ‘Truce Talks’ of being ‘inherently phony.’ Activist Marilyn Szewczyk told Smeal that she ‘totally and absolutely support[ed] the actions taken… and only wish[ed] I could have been there and supported them in person’. March for Life organizer Nellie Gray helped bury the two fetuses the morning after the protest. And Lois Fraser and Bob Fraser of PEACE-Cleveland, who were involved in acquiring, baptising, and naming the fetuses, praised the act as revolutionary and posited that because, of three women’s intervention, ‘for the first time in the pro-life movement, the unborn spoke in defense of the unborn, “I am here – here I am”’. Clearly, for these anti-abortion activists, the mere suggestion of engaging in civil discussion with pro-choice activists caused great offense, and justified PEACE-Cleveland’s radical intervention.

However, other anti-abortion activists were quick to denounce PEACE-Cleveland’s actions as disgraceful and unjustifiable. Immediately after the meeting, Juli Loesch Wiley expressed ‘the enormous shame and sorrow’ she felt in the wake of the incident, sharing with NOW event organizers that ‘Far from being “pro-life”, I think their use of a dead body as a “prop” for a piece of media theatre was an act of disrespect bordering on sacrilege… I experienced in their action the very spirit of violence.’ Members of the Pro-life Nonviolent Action Project (PNAP) and PEACE-St. Louis were also quick to assure NOW ‘that at no time were we informed by the Cleveland PEACE group of their intended action’, and expressed hope ‘that the incident will not damage the possibility of continuing our dialogue’. Some members of PNAP, PEACE-St. Louis, and Feminists for Life even ‘agreed to have a private day of prayer and fasting to atone’ for their fellow right-to-lifers’ ill conduct. Yet other attendees remained optimistic about future opportunities for collaboration. Eleanor Smeal described PEACE-Cleveland’s intent to sabotage the meeting as an ‘isolated incident’ that ran counter to the ‘good atmosphere of the conference’. And, harnessing the rhetoric of second wave feminism, Loesch Wiley signed a letter to NOW’s Action Center with ‘Sisterhood is possible… [From] your friend’. The anti-abortion activist was especially enthusiastic about ‘using the insights and energies of both “pro-life” and “pro-choice” people to aid women and reduce the numbers of abortions’.

Juli Loesch Wiley was not alone in hoping that a joint commitment to bettering prenatal and postnatal care could bring pro-choice and anti-abortion activists together. In 1990, for instance, opposing sides of Webster v. Reproductive Health Services (1989), the US Supreme Court decision that upheld a Missouri law restricting the use of state funds in abortions, came together to improve material conditions for women and children in their city of St. Louis, Missouri. Their ventures included working to streamline adoption services and supporting a state bill to help pregnant women suffering from drug addiction. These efforts contributed to the creation of the Common Ground Network for Life and Choice in 1993. Throughout the 1990s, the Network fostered opportunities for pro-choice and anti-abortion activists to come together in the pursuit of common goals, such as reducing the abortion rate – also a chief goal of Smeal’s 1979 meeting.

Although the melodramatic end to the 1979 NOW meeting appears to repeat an oft-told story about the irreconcilable differences between pro-choice and anti-abortion activists, a closer inspection illuminates concerted efforts to bridge the divide of the abortion wars. By putting the absolutes of abortion legality aside, Eleanor Smeal illuminated ways that abortion activists might find consensus. In this endeavour, she was not alone. Negative and fierce reactions notwithstanding, some activists did find ‘common ground’ on abortion and related reproductive issues in the concluding decades of the twentieth century. Finding commonality on topics such as lessening the abortion rate, stamping out violent extremism, and providing women with viable reproductive options other than abortion, they demonstrated that consensus could be found even in the most volatile of conflicts. While abortion remains as contentious an issue as ever, the longstanding efforts of common ground proponents reminds us that the divisive rhetoric propagated by the US abortion wars was not, as is not, representative of all activists.

Author Biography

Isobel Bloom is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her dissertation is a history of anti-abortion activism in the late-twentieth century United States.

Further Reading

Karissa A. Haugeberg, Women Against Abortion: Inside the Largest Moral Reform Movement of the Twentieth Century (University of Illinois Press, 2017).

Krista Tippett, interview with David Gushee and Frances Kissling, Pro-life, Pro-choice, Pro-dialogue. Podcast audio. On Being: Civil Conversations Project (2012). 51:24 [https://onbeing.org/programs/david-gushee-frances-kissling-pro-life-pro-choice-pro-dialogue-2/].

Robin West, Justin Murray, and Meredith Esser (eds.), In Search of Common Ground on Abortion: From Culture War to Reproductive Justice (Routledge, 2014).

Mary Ziegler, After Roe: The Lost History of the Abortion Debate. Cambridge, Massachusetts (Harvard University Press, 2015).