Coal: From ‘Who Governs?’ to ‘What Governs?’

- EPOCH

- Aug 31, 2024

- 6 min read

C. Robert Rayner | University of Birmingham

In February 1974, a general election was reluctantly called by Prime Minister Edward Heath in the midst of an energy crisis that threatened to ‘turn the nation’s lights out’. Not only had the oil price quadrupled since October, but Britain’s coal miners were seeking a pay rise in breach of the government’s statutory incomes policy. Heath’s narrow defeat on 28 February was to mark the end of his ‘One Nation’ style of Conservatism with Margaret Thatcher replacing him as party leader a year later.

More significantly the election is remembered as a victory for the miners and for their union, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM). The Conservatives had gambled on the public backing their firm stance on pay and union militancy but were proved wrong. Rather, the British public and the wider trades union movement broadly supported the miners being treated as a ‘special case’. This point had been ceded after the earlier miners’ strike of 1972, which had been settled following an independent pay inquiry chaired by Lord Wilberforce.

As the above cartoon suggests, the history of this key election is invariably framed around class conflict, specifically the confrontation between a Conservative government and a powerful group of workers. This narrative is commensurate with a broader collective memory of the seventies as a period in which the postwar political consensus was being broken in the face of industrial decline and strife. It is also worth remembering that many of those involved with the coal disputes of the period would become leading protagonists during the 1984/85 miners’ strike, not least Margaret Thatcher and Arthur Scargill.

However, historians are starting to take an interest in the concept of New Materialism as a way of providing an alternative perspective on social, economic, and political change. Central to this way of thinking is a willingness to accept that ‘matter matters’ and that seemingly inanimate objects can and do have the ability to influence and shape human behaviour, organisation, and wellbeing. It encourages historians to view ‘things’ not as passive bystanders in the human story, but as inexorably interwoven and contributing to it.

A good example of where new materialism has been meaningfully applied is within labour studies, where work and the environment are interlinked. This resonates with the growing academic interest around occupational health and work-related disability, which focuses on the inter-relationships between jobs and bodies. Coal mining therefore provides something of an obvious case study for those keen to explore the potential for matter to shape the organisation and wellbeing of not only individual workers but whole communities.

My research journey begins with the miners’ disputes of 1972 and 1974. Both strikes were similar in nature and their associated pay inquiries both emphasised the unique nature of the miners’ working environment. For example, the Wilberforce Report of 1972 concluded:

The large group of men underground do work which is heavy, dirty, hot and frequently cramped. Other occupations have their dangers and inconveniences, but we know of none in which there is such a combination of danger, health hazard, discomfort in working conditions, social inconvenience and community isolation.

And the Pay Board’s report of 1974 re-emphasised this sentiment:

We examined two particular aspects of coal mining which might be thought to justify exceptional treatment… The second aspect concerns the adverse conditions, the arduous nature of the work, the risks and health hazards involved.

New materialism offers an alternative understanding of what led to the renewed militancy of the miners and ultimately the ‘Who Governs’ general election. The antecedents of the strikes can be tracked to the role that machines played. By 1970, ninety percent of Britain’s coal faces were mechanised which changed the working practices of miners and the environment in which they worked. The traditional image of the miner with his pickaxe and shovel was superseded by the ‘modern miner’ as a machine operator or technician, something that was formally acknowledged in the landmark National Power Loading Agreement (NPLA)of 1966. Along with the nationalisation of the mines in 1947, this was arguably the key turningpoint for Britain’s coal industry in the twentieth century.

At the time both the National Coal Board (NCB) and the NUM welcomed the agreement as securing the long-term future of the industry after a decade of decline. It was supposed to equalise pay rates throughout Britain’s geologically different coal fields and ensure future national pay bargaining, overcoming historic area-specific disputes. It was designed to gradually do away with the old ‘piece work’ system in favour of a national day rate for the job. The former had been fundamental to Britain’s mining industry since its inception, where miners were paid for how much coal they hewed. National pay rates were seen as a more equitable system for remuneration and helping to unite miners within and between collieries.

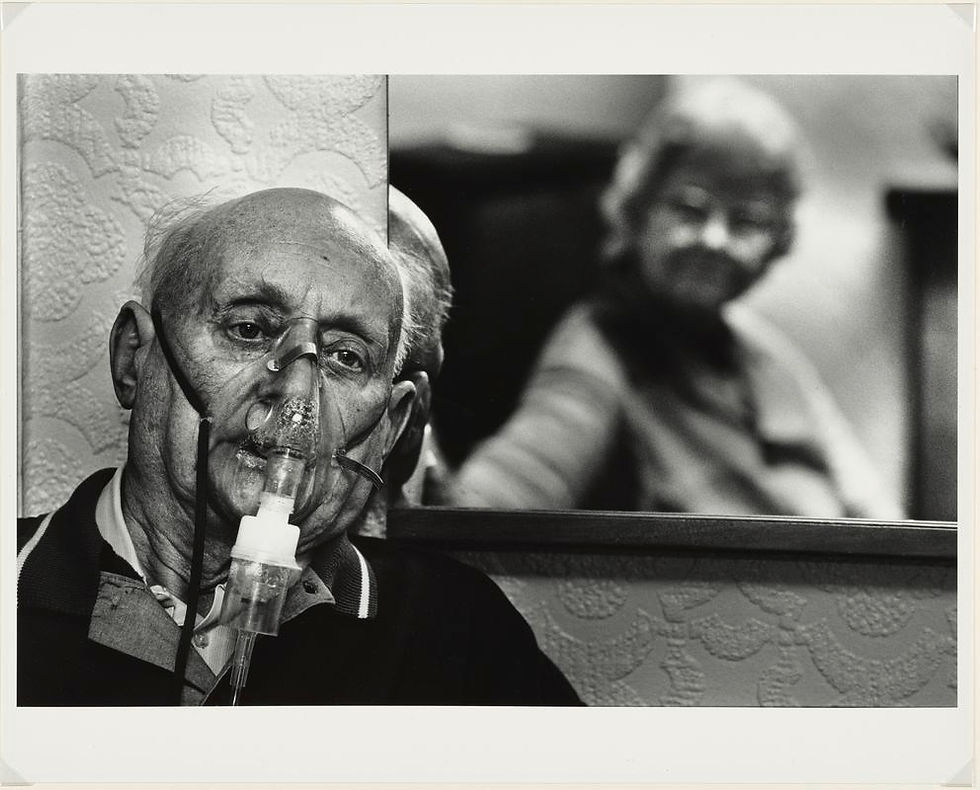

However, a more important and unintended consequence of mechanisation related to the working environment itself: specifically, the amount of dust, noise, and fumes generated. Coal and rock dust were insidious, the single biggest killers and disablers of the underground miner, far more than the sporadic pit disasters that would catch the public headlines and then fade away. Chronic respiratory disease, notably silicosis and coal pneumoconiosis (Miners’ Lung), led to a debilitating cough and breathlessness that progressively weakened the body and impaired quality of life. Bronchitis and emphysema were belatedly added to the list of prescribed respiratory diseases for coal miners in 1993.

If coal itself - the ‘deadly dust’ - could undermine a miner’s health, then machines were inadvertently to make things worse for the underground worker. The machinery generated significantly more dust and introduced new dangers, such as Vibration White Finger (VWF) and Noise Induced Hearing Loss (NIHL), that were only diagnosed decades later.

Following legal cases in the late 1990s, the British Government was forced to introduce compensation schemes for retired miners and their dependents in respect of respiratory disease, VWF, and industrial hearing loss. Initially the government and the ex-coal authority expected around 70,000 cases. By the time the schemes closed over 750,000 claims had been submitted totalling over £6 billion, making it the largest occupational compensation scheme in British and European history. An interesting footnote to these legal cases was the prominent campaigning played by the current Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer in respect of VWF.

The Wilberforce and Pay Board reports were progressive, and ground-breaking, in recognising that the working environment should count as a factor in the relative pay of manual workers. They also traced the decline in miners’ wages of the late 1960s to the impact of machinery on the industry. Critically they brought into consideration the idea of ‘occupational health’ by embracing a proto-new materialism perspective, namely the hazardous effect matter has for debilitating the human body. One of the overlooked facts from the 1974 miners’ settlement was the subsequent introduction of the largest ‘no fault’ compensation scheme in Britain, the Coal Workers Pneumoconiosis Compensation Scheme (July 1974).

While the government begrudgingly accepted the Wilberforce Report, it doggedly refused to restore miners’ relative pay eighteen months later. The irony being that it was only after Heath had called the election that the government decided once again to submit the miners’ pay claim for independent recommendation. By the time the Pay Board’s report was published three weeks later, Labour under Harold Wilson had returned to power and the dispute was settled within days. Notably, the Pay Board had recommended that a unique ‘underground allowance’ payment should be introduced in recognition of the likely damage to a miner’s future health and wellbeing.

This article has shone a brief spotlight on new materialism and the potential value it can have for historians looking at change from a different perspective. The coal strikes of 1972, 1974, and 1984/85 are invariably told through the lens of industrial relations and class conflict. But the mechanisation of the mines illustrates how difficult it is for governments, unions, medical professionals, and scientists to predict how things will affect human practice and change the course of history. At the time the introduction of the NPLA was seen as a positive move, but in reality it suppressed underground pay which largely contributed to the renewed militancy of miners in the early seventies. More fundamentally, mechanisation added unforeseen dangers that would contribute to Britain’s ‘largest occupational health disaster’.

By focussing on ‘things’, the February 1974 election narrative moves away from the traditional question of ‘Who Governs?’ to embrace a broader ‘What Governs?’ understanding. While most mining communities and left-wing commentators continue to hold Margaret Thatcher responsible for the final demise of the industry, a new materialism perspective suggests that it is machines and coal itself that have left the more profound social legacy.

Further Listening:

Ewan MacColl, Peggy Seeger and Charles Parker, The Big Hewer: radio ballad (Decca Records, 1967).

Further Reading:

Arthur McIvor, Jobs and Bodies: An Oral History of Health and Safety in Britain (Bloomsbury Academic, 2024).

Dominic Sandbrook, State of Emergency: The Way We Were: Britain, 1970-1974 (Penguin, 2011).

Jane Bennett et al, New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics (Duke University Press, 2010).

John Hughes, Roy Moore and National Union of Mineworkers, A Special Case?: Social Justice and the Miners,Cmnd.4903 (Penguin, 1972).

William Ashworth, The History of the British Coal Industry: Vol 5; 1946-1982: The Nationalized Industry (Clarendon Press, 1986).

Having previously studied Geography (BA, 1985-88) and Marketing (MA, 1990), Robert has spent most of his working career involved in marketing and marketing research. He has returned to higher education at Birmingham University (MRes History) with an interest in postwar British politics, focussing on 1964-1979. As the grandson of a South Wales miner, his studies are increasingly drawn to the socio-economic, cultural, and political changes of the period through the lens of the British coal industry. He presented this paper at Lancaster University’s PGR HistFest 2024.

Birmingham University PGR Poster Competition 2024: entry