Charmaine H. Lam | University of St Andrews

Think about piecing a puzzle together. You have a general idea of what the final product might look like, and you’ve seen completed puzzles that you think might look like yours, but you don’t have all the pieces of your puzzle. That should give you a decent idea of what conducting research in imperial history is like.

This puzzle analogy applies to a recent shift in imperial historiography, which historian Durba Ghosh has termed the “imperial global turn”.This shift marked a departure from the traditional approach to imperial history, which followed a top-down approach that drew from archival material organised and created by imperial governments – French administrative documents in Algeria, for example, or import and export statistics of the British East India Trading Company.

In the late 2000s, imperial historians began to move away from this Eurocentric perspective to write a more decentred narrative of world history and imperial history that considered, for example, the political action of Indian peasants under British rule or the ways in which Chinese domestic servants in Britain’s Southeast Asian colonies challenged the power of their British employers and of the larger imperial structure.

While this turn has presented great opportunities for imperial history, it has also presented new challenges. It has allowed for a focus on the social and cultural aspects of colonised peoples that continue to shape our societies today, presenting opportunities for greater public engagement. However, the research process has also highlighted the difficulty of navigating source material to access voices and stories that were silenced in the oppressive imperial network.

Scholars across the humanities and social sciences have pointed to the difficulty of accessing the colonised subjectivity, which has been termed the “subaltern” perspective. Historian Clare Anderson described the fragmented nature of conducting such research in her book dedicated to subaltern lives in the British Empire. She argued that the incompleteness of the source material for such research was key in revealing “the disciplinary intent and partiality of the archive” as well as the “unequal distribution of power in colonial societies”. To piece together the histories of the subaltern perspectives, fragmented source material must be “assembled and then collated to construct snapshots of at least part of [the subaltern’s] lives and social worlds”.

Given the fragmented nature of the source material when it comes to the non-elite, colonised narratives within imperial history, the question has turned to how historians can fill these gaps to still produce research of rig our and significance. The more important question, however, should be: how can historians produce rigorous and significant research in imperial history that engages its audience?

This is particularly pertinent to imperial history, the impact of which continues to reverberate in the present. Current issues such as racial inequality and prejudice in the UK and political tumult in Hong Kong can trace their origins to Britain’s imperial past. This impact has been addressed in discussions of history within field sat the forefront of public engagement, such as heritage interpretation, in which museum visitors are encouraged to engage personally with the primary source material on display. However, there is yet much room for such discussion within academic publication of imperial history, for which the public is not seen as the primary audience.

So, what is the role of communication in academic history, and what sets it apart from fields like popular history or even historical fiction? Historian William Cronon emphasised the critical role rigour plays in academic history in his AHA Presidential Address “Storytelling.”

While Cronon argued that the “essential mission of history” is to “[keep] the past alive for the wider public,” he maintained that history must be grounded in evidence. As historians, he said, “we are not permitted to argue or narrate beyond the limits of our evidence”. If it cannot be supported by such evidence, it cannot be considered academic history. (The limitations of what can be considered substantive evidence is also still shifting within academic histories, such as in the treatment of oral histories.)

Especially in the way it is taught, not only in compulsory education but even at the university level, academic history tends to neglect narrative components for this evidence-focused rigour. While this eliminates the ability for historians to, like writers of historical fiction or even popular history, create characters with inner voices that invite the reader directly into their worlds, this poses particular problems for the historian of empires and their colonies.

For these historians, source materials are limited because the empires themselves established systems to quell the voices and heterogeneous identities of the colonised in order to stabilise their rule. It is hard enough, then, to find source material that tell colonised stories and even harder to put together a compelling narrative that is not in some way embellished as the historian seeks to fill the frequent and sizable gaps in the archives.

It is not only the dearth of official source material, but often language and cultural differences, that make it impossible to study these stories from the research framework of modern-day, Western-developed academia. For example, historian Eloise Grey’s research on the emotional communities within transimperial and mixed-race families relied largely on letters in translation to understand the dynamics of such an illegitimate family within the British East India Trading Company. Not only can the voice of the Indian woman in question be gleaned solely through these letters, but they were also translated and recorded by someone else and thus do not present her original voice.

It is hard enough, then, to find source material that tell colonised stories and even harder to put together a compelling narrative that is not in some way embellished as the historian seeks to fill the frequent and sizable gaps in the archives.

It is here that academic history of empires has much to borrow from heritage interpretation. In 2017, the Bristol Archives collaborated with the Bristol Museums to curate an online exhibition called Empire Through the Lens that is available to access here. The exhibition curated a selection from the British Empire & Commonwealth collection, which spans the temporal and spatial span of the empire. The Bristol Archives describes the collection as “the household belongings, souvenirs, photographs and papers of British people who lived and worked in the colonies” that “give an insight into the workings of empire and the lives of the people who made it function.” (Link to the archival collection here.)

The exhibition took the overwhelming 500,000 photographs and 2,000 films that make up the collection and presents twenty-seven pieces to its audience. It drew its curators from academics to artists, development workers and family members of colonial workers – from individuals whose personal and professional lives have been impacted by the legacy of British imperial history.

The ties these selectors have to the exhibition’s theme permeate the visual material chosen and the blurbs each selector wrote to present how they view the piece and the legacy of empire. In so doing, the exhibition engages the public directly with primary source material, bypassing issues of transparency and accountability in dealing with source material often seen in popular works of history. Further, it guides its audience past the immediately obvious imperial narrative presented in the visual material, which, like many other such source material,is part of a historical archive that was collected and organised through the white, colonial elite perspective.

The photographs were taken by the colonial elite of their servants and labourers – of indigenous peoples who, in these pictures, were represented in their hierarchical, colonial relationship with the white photographers. By presenting these photographs through the lens of people who, in the present, have been impacted by this oppressive legacy of empire, the exhibition brought the living world of history closer and in a much more personal and impactful way to its audience.

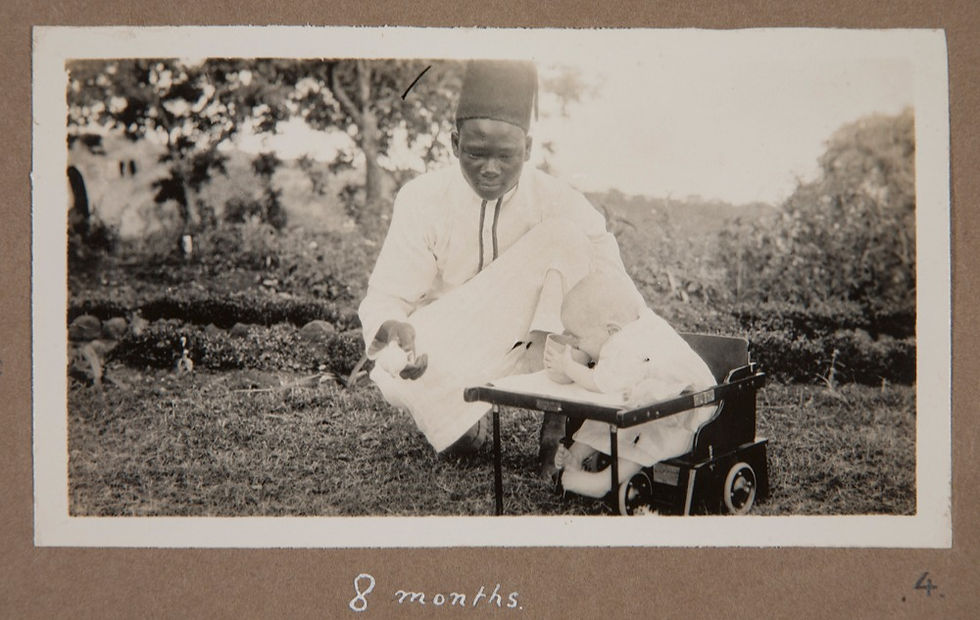

These pictures and their accompanying blurbs point to ways that historians can incorporate heritage interpretation and digital tools to engage a wider audience in imperial history. They both prompt active engagement, as with the selection of the picture “Letembia and Ann Chandor”, which depicts a native servant taking care of a British baby in Tanzania, for example. In the blurb, historical anthropologist Elizabeth Edwards asked the audience to consider “the ambiguity of personal relations within the colonial system.” The photograph depicts the inequalities of the colonial system, yet Edwards pointed to the “tenderness, care, and even perhaps affection” in the picture.

Other selections more strongly emphasised the perspective of the colonised and oppressed. “These Water Melons” depicts seated indentured Jamaican labourers eating watermelon on a break from work. However, the photo’s selectors, artists and curators Kat Anderson and Graeme Mortimer Evelyn, pointed to the unseen systems of oppression at work in the photo’s creation. They prompted the audience to “consider the image from both the photographer’s and sitters’ perspectives.” Although the scene depicted may seem “benign or even jovial,” Anderson and Evelyn pointed out that “the young sitters photographed would have sat motionless for 15 minutes for light to be exposed to the print.” Upon closer look, the audience can make out “bored and tired expressions” on the boys’ faces that reflect “an understanding that they are being made fun of.”

Blurbs like these highlight the ambiguities of colonial histories that stem from the skewed perspective of available archival material. It is difficult, then, for historians to construct any semblance of a complete imperial history were we to hold ourselves firmly to that which historical evidence tells us must be true. We can, however, bring aspects of heritage interpretation into the research methodology of academic history and use these ambiguities to construct a more accurate picture of history.

It is important for academic historians of imperial history to embrace the uncertainties that define the field and to use these uncertainties to highlight the oppressive structures that characterise the world of empires.

In a study of a slave woman’s agency and resistance in seventeenth-century Manila, for example, historian Susan Broomhall openly acknowledged the need to “‘read against the grain’ and into the ‘cracks’ of the documents’ original purposes within colonial and ecclesiastical communication networks”. Throughout her analysis, she used verbs like “hint at” or “suggests” as she used source material to try to uncover the life of Maria the slave. After presenting her evidence and what they might be able to illuminate, Broomhall openly posed questions of her reader to engage them in thinking through the source material. After presenting archival material about Maria’s relationship to her master and the actions taken on her behalf by other community members, Broomhall asked her readers to consider: “Was the relationship exploitative and/or violent, or had Maria determined that she would be better looked after as the house-hold property of an elite woman…?”

By so engaging the reader, this approach to academic history encourages the reader not only to consider how the evidence supports the historian’s argument, but also to consider the perspective of the colonised, non-elite historical agent. As in heritage interpretation, the questions here guide and prompt a more personal understanding of the stories that have unfolded throughout history.

Not only does such an approach highlight the silenced voices and narratives that make up imperial history, but it also addresses the problems posed by the fragmentary nature of the source material. Historians must embrace uncertainty, and there must be room made for uncertainty that does not detract from the rigour of historical research and analysis.

It’s only through this that we can acknowledge the fragmented nature of the source material and write histories that not only engage the public to consider the impact history continues to have on the present, but that subvert the hierarchical and oppressive structures in which imperial histories occurred.

----------------------

Further reading

Anderson, Clare, Subaltern Lives: Biographies of Colonialism in the Indian Ocean World, 1790-1920 (Cambridge: Cambridge Press, 2012)

Bristol Museums, Empire Through the Lens, https://exhibitions.bristolmuseums.org.uk/empire-through-the-lens/

Broomhall, Susan, ‘Voicing Sexual and Social Resistance in Seventeenth-Century Manila’, in Subaltern Women’s Narratives: Strident Voice, Dissenting Bodies, ed. By Samraghni Bonnerjee (London: Routledge, 2021).

Cronon, William, ‘AHA Presidential Address: Storytelling’, https://www.historians.org/about-aha-and-membership/aha-history-and-archives/presidential-addresses/william-cronon.

Grey, Eloise, ‘Natural Children, Country Wives, and Country Girls in Nineteenth-Century India and Northeast Scotland’, Historical Reflection 47, no. 1, pp. 31-58.

Charmaine H. Lam is an MLitt Transnational, Global and Spatial History student at the University of St Andrews. Her research interests centre on the British Empire, and she's particularly interested in the transnational networks and movements of colonised, non-elite groups therein.

Twitter: @charmainehlam