Josh Coulthard | Edge Hill University

The year is 1295, and the residents of Clydesdale, about four miles from Paisley, live in fear.

The hideous reanimated corpse of an excommunicated monk from the nearby Paisley Abbey stalks day and night. Upon arriving at the castle of Sir Duncan de Insula, his household attempted to drive out the creature, but all to naught. Whenever they tried to slay it, whether by stabbing it with pitchforks or shooting arrows at it, their weapons were burnt to ashes in seconds. In return, those who traded blows with the creature were so savagely battered that all their joints were shattered. One night, while Sir Duncan and his household were seated around the hearth, the creature burst into the castle, throwing objects at them and attempting to land blows. Fearing for their lives, the household fled the castle. Only Sir Duncan’s eldest son remained to fight the creature in single-handed combat. His mangled corpse was discovered the following morning. The creature was never seen again.

In summing up, the chronicle states:

Wherefore, if it be true that a demon has no power over anybody except one who leads the life of a hog. It is easy to understand why that young man came to such an end.

Stories such as this are common in the first part of the Lanercost Chronicle, compiled by Richard of Durham around 1298 against the backdrop of the First Scottish War of Independence. They serve a clear narrative purpose; by crafting a compelling example, they demonstrate their author's religious and political messages. Breaking down the original text shows us one of the clearest instances in the Chronicle of relating biblical allegory to the perceived injustice of the war. Lanercost promises to tell us of ‘something equally horrible and marvellous’ which happened in Clydesdale, the function of this tale he tells us is ‘to strike terror into sinners’.

The chronicler tells us, ‘When men either shot at him with arrows or thrust him through with forks, straightway whatever was driven into that damned substance was burnt to ashes in less time than it takes to tell it. Also, he so savagely felled and battered those who attempted to struggle with him as well-nigh to shatter all their joints’. This is a clear exhortation to peaceful resistance of aggression, whereby the author is asking his readers not to violently resist but rather place their faith in God and trust in their moral character as ‘a demon has no power over anybody except one who leads the life of a hog’ reflecting the medieval stereotype that hogs were violent and destructive creatures.

It is apparent from the text that this is the purpose of recording this incident as it appears alongside a spate of other supernatural portents recounting the failures of the king of England’s enemies, starting with the decision by the Scots to enter into ‘active rebellion and to repudiate the homage done to King Edward [I], devising how they should enter into a treaty with the King of France so that they should harass England between them’, a sequence which ends with the King of France sending out his ships which are destroyed by winds of the coast of Dover due to supernatural the protection of the Virgin Mary.

To briefly explain the cultural context in which the compilers of the chronicle were brought up it is worth going back to the period just after the Treaty of York (1237), which fixed the border between Scotland and England at roughly where it is today, resulting in a century of peace between the kingdoms of England and Scotland. However, we should understand the border as essentially porous. Relations at this time between the Northern English and Lowland Scots were incredibly close, especially in Northumberland, where landholders held Scottish and Northumbrian land while landholders from the rest of England held little land there. This situation would remain largely unchanged until 1296, when Edward I ordered the arrest of all Scots living in England. This order not only highlights the emergent distinctiveness of Scottish nationality but also reveals that many Scots had lived unnoticed in England up to that point. Previously inconsequential personal ties between families on either side of the border now forced them to take sides.

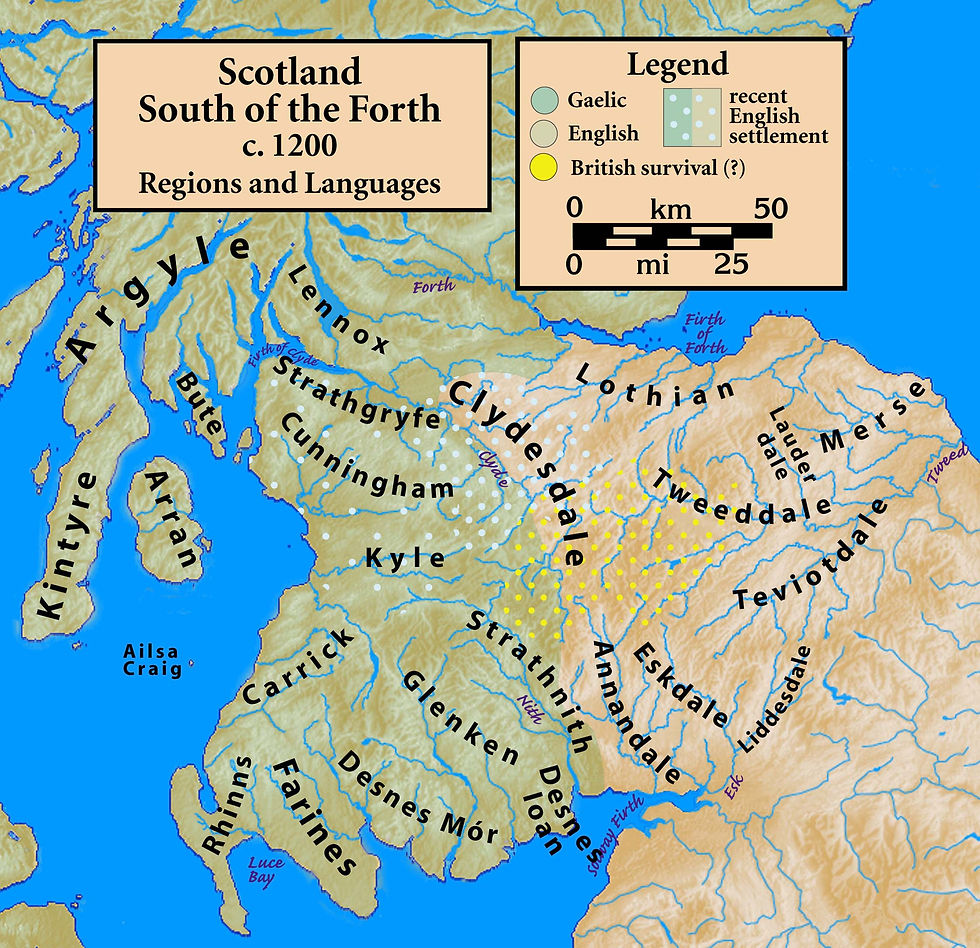

However, the divisions between the Scots and English are not the only story worth examining. Within Scotland, there was a clear fracture between the Gaelic inhabitants of Galloway in southwestern Scotland and the Scots of south-eastern Scotland, who spoke Anglo-Norman French and a variant of Middle English known as Scots. Galloway had only lost its independence during the 1230s following a succession crisis in the erstwhile kingdom. However, within this region, many marriages were mixed, as demonstrated by the parentage of John de Balliol. His mother, Dearbhfhorghaill, was the daughter of Alan of Galloway, the last independent ruler of Galloway, while his father was the lord of Barnard Castle in County Durham.

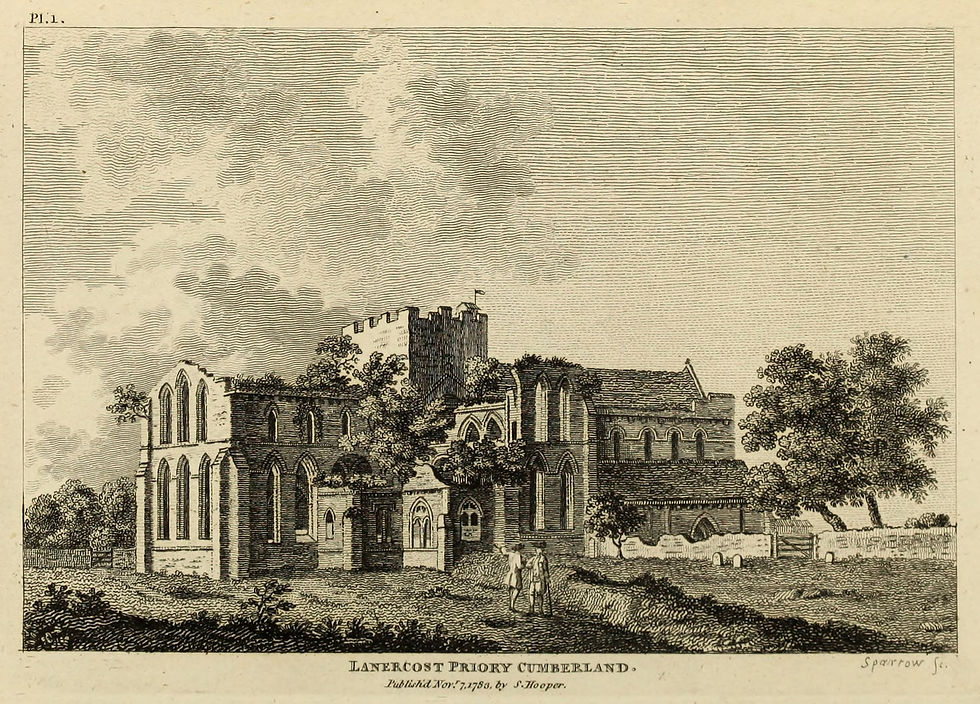

So why look at Lanercost? The unique perspective offered by the friars of Lanercost rests on their position in an extremely porous border region subject to its own mixed border laws. No religious house in Cumbria was more frequently burned by the Scots, and no district underwent more pillage than Gilsland, which is to the east of Carlisle. Furthermore, the canons had property in Carlisle, Hexham, Newcastle, Mitford near Morpeth and Dumfries, and Cumbria itself had only been incorporated fully into the Kingdom of England during the mid-twelfth century.

Lanercost provides us with its most interesting insights when it grapples with violence. The problem of violence vexed later medieval England as the gap between the reality of a violent, militaristic society and the ideals of chivalry, which stressed honour and prestige above violence, proved a difficult circle to square.

Turning to the second part of the Chronicle, attributed to Thomas of Otterbourne, we can once again see how it is uneasy about the injustice of war.

This unease is strikingly evident in its treatment of Andrew de Harcla, the Earl of Carlisle, who was executed in 1323 for making a unilateral peace deal with Robert the Bruce. The chronicle makes clear its stance by stating, ‘albeit he merited death according to the laws of kingdoms, his aforesaid good intention may yet have saved him in the sight of God’. The chronicle declares that the ‘Earl of Carlisle perceived that the King of England neither knew how to rule his realm nor was able to defend it against the Scots, who year by year laid it more and more waste, he feared lest at last [the king] should lose the entire kingdom; so he chose the less of two evils, and considered how much better it would be for the community of each realm if each king should possess his own kingdom freely and peacefully without any homage, instead of so many homicides and arsons, captivities, plunderings and raidings taking place every year’. Here again, we see a preference for nonviolence and peace, favouring peace on terms that favour the Northerners no matter how much it may put out the King of England.

However, the need to justify war against a fellow civilised and chivalric society resulted in the calling up of tropes associated with warfare against the supposedly barbarous Welsh, Irish, and Gaels. That we see this throughout the chronicle demonstrates the lingering goodwill towards the Scots from the Northerners.

At the start, the chronicle’s condemnation is directed firmly at the men of Galloway rather than the Scots. In one passage, they are described as surpassing ‘in cruelty all the fury of the heathen’ and as ‘apt scholars in atrocity’, thereby presenting them as outside of the realms of chivalry, declaring ‘the devastation can by no means be attributed to the valour of warriors, but to the dastardly conduct of thieves.’ These tropes were commonly deployed against the Celtic inhabitants of Britain and Ireland by medieval English authors. This can be compared with the descriptions of the people of Berwick, who are described simply as ‘misguided people’ for joining the Scots against the English. Robert the Bruce’s forces at the Battle of Byland (1322) meanwhile are described as fighting ‘fiercely and courageously’, while the English are derided for their failure. The aftermath of this battle even sees the chronicle describe Robert as king of Scots for the first time.

Throughout the short verses contained within the chronicle, there is a consistent theme that the Scottish are not inherently evil, simply misguided. This is clear from a verse playing on the meaning of William Wallace’s name ‘Welsh William’ in which the verse states;

Welsh William being made a noble, Straightway the Scots became ignoble. Treason and slaughter, arson and raid, By suff'ring and misery must be repaid.

The chronicle holds a particularly negative opinion of this ‘certain bloody man, William Wallace’. It labels him as ‘formerly a chief of brigands’, taking a great and morbid interest in Wallace’s victory at Sterling Bridge, describing how he ordered that Hugh de Cressingham’s skin be taken in a broad strip ‘from the head to the heel, to make therewith a baldrick for his sword’. It further highlights that when Wallace took Scottish castles back from the English, he promised them safe passage out of the castles and then betrayed this promise immediately after.

Its response to Wallace’s execution is equally enlightening;

The vilest doom is fittest for thy crimes, Justice demands that thou shouldst die three times. Thou pillager of many a sacred shrine, Butcher of thousands, threefold death be thine! So shall the English from thee gain relief, Scotland! be wise and choose a nobler chief.

While this is the last time Wallace appears in the chronicle alive, his severed head does make a number of appearances later in the chronicle. By associating Wallace with the Welsh, the poet intends for us to view Wallace as a foreigner who has no connection to Scotland, building upon the frequent references throughout the chronicle to the Welsh’s constant rebellions, ‘untrustworthiness’, and ‘long-standing spite’ thereby justifying any violence against Wallace.

Near the end of the chronicle, we see that this resistance to directly laying the blame on the Scots is gone. This is immediately clear in David II’s battlefield execution of Walter de Selby, which is depicted as an act beyond the bounds of chivalric warfare, reflecting the barbarousness of the Scots through religious allegory. In the scene, de Selby cries out to David, ‘O king, greatly to be feared! if thou wouldst have me behold thee acting according to the true kingly manner, I trust yet to receive some drops of grace from the most felicitous fountain of thy bounty’ but David like ‘another Pharaoh, raging, furious, goaded to madness worse than Herod the enemy of the Most High’ orders his men who are described as ‘limbs of the devil’ and ‘the tyrants’ torturers’ to slay him, the chronicler ending the scene with disgust against them as they ‘wickedly and inhumanely caused human blood to flow through the field.’ Here the chronicler shows the villainous nature of David by comparing him with two key biblical villains, the Pharaoh who refused to release the Jews from Egypt and Herod, the king of Judea who ordered the death of all the newborns of Judea to try and prevent Jesus from growing to become King of the Jews.

The emotional resonance given to this sets up the final action of the chronicle, Edward III’s resounding victory at the Battle of Neville’s Cross (1346). The incongruity of the demonisation of David II compared to the rest of the chronicle perhaps reflects the insertion of propaganda produced by the court of Edward III during his campaign against David. In summing the battle, the chronicle offers this summation, ‘the flower of Scotland fell, by the just award of God, into the pit which they themselves had dug’. The war was now firmly justified.

*I thank Tom Johnson, who supervised the research on which the article is based as a master's dissertation at the University of York in 2023.

Further Reading:

Herbert Maxwell, trans., Chronicle of Lanercost 1272-1346 (Glasgow: Glasgow University Press, 1913). Available freely online at https://archive.org/details/chronicleoflaner00maxwuoft

J.A. Tuck, ‘Northumbrian Society in the Fourteenth Century’, Northern History 6 (1971), 22-39.1

Andy King, ‘Englishmen, Scots and Marchers: National and Local Identities in Thomas Gray's Scalacronica’, Northern History 36, (2000), 217-231.

A.G., Little, ‘The Authorship of the Lanercost Chronicle’, The English Historical Review, 31, (1916), 269-279.

Michael Brown, Disunited Kingdoms Peoples and Politics in the British Isles 1280-1460 (Harlow: Pearson, 2013).

Josh Coulthard is a doctoral candidate at Edge Hill University. His research focuses on the political culture of the insular Plantagenet World between 1200 and 1400; he is especially interested in the intersection between identity and social memory. He is also the co-convenor of the North West Medieval Studies Postgrad Reading Group [https://northwestmedieval.com/].